NEUROENDOCRINE TUMOURS

WHAT ARE THEY?

The human body is made up of billions of cells, from blood cells to brain cells. Neuroendocrine cells are found throughout the body across a network called the neuroendocrine system. Cells of the neuroendocrine system produce hormones (endocrine action), usually in response to signals from other cells or from the nervous system (neurological stimulation). All neuroendocrine cells release hormones and other chemicals into the blood, helping our bodies to function normally.

Cells of the neuroendocrine system produce hormones (endocrine action), usually in response to signals from other cells or from the nervous system (neurological stimulation). All neuroendocrine cells release hormones and other chemicals into the blood, helping our bodies to function normally.

Neuroendocrine tumours or NETs is an umbrella term for tumours that originate in cells of the neuroendocrine system causing it to stop functioning normally. These tumours are rare: they only occur in around 4 to 5 in 100,000 people every year.

They are usually less aggressive, slow-growing tumours. This is why NETs are often only diagnosed when the disease has already reached an advanced stage. Diagnosis is difficult due to the many different types of neuroendocrine tumours and their non-specific symptoms that resemble those of other common conditions.

However, thanks to research, improved diagnostic techniques and better patient management, knowledge of NETs is improving.

Key Points

FREQUENCY OF NETS

- NETs make up 2% of all cancers

- They affect both men and women

- Average age at the time of diagnosis: 50 to 60 years old

MOST COMMONLY AFFECTED ORGANS

- Digestive system (stomach and intestine)

- Pancreas

- Lungs

COMMON SYMPTOMS

- Diarrhea

- Skin flushing (face)

- Bloating

- Stomach pain

- Wheezing

AVERAGE DIAGNOSTIC DELAY

- 5 to 7 years

Detecting the disease

In cases where the neuroendocrine tumour is said to be “functional”, it causes an excessive secretion of hormones which may lead to its detection. The patient may experience symptoms which cause them to visit a doctor. These symptoms vary depending on the location of the tumour; they may include, to name a few, painful abdominal cramps, diarrhoea, sudden facial flushing or even hypoglycaemia.

However, in the majority of cases, as the neuroendocrine tumour is “non-functional”, it may only be noticed by the patient when it’s large enough to affect or compress the organs concerned. At this point, symptoms such as stomach ache, jaundice, bowel obstruction or weight loss may occur.

The tumour might also be discovered accidentally during surgery or a routine examination (imaging, colonoscopy, etc.) carried out for other reasons.

Finally, a small number of endocrine tumours – less than 5% – are genetic.

TYPES OF NETs

NETS are named and treated according to the organ in which they originate, even if they have spread to other organs. The first organ to be affected by NETs is considered the “primary” or “main cancer site”.

PRIMARY NET OR UNKNOWN PRIMARY NET

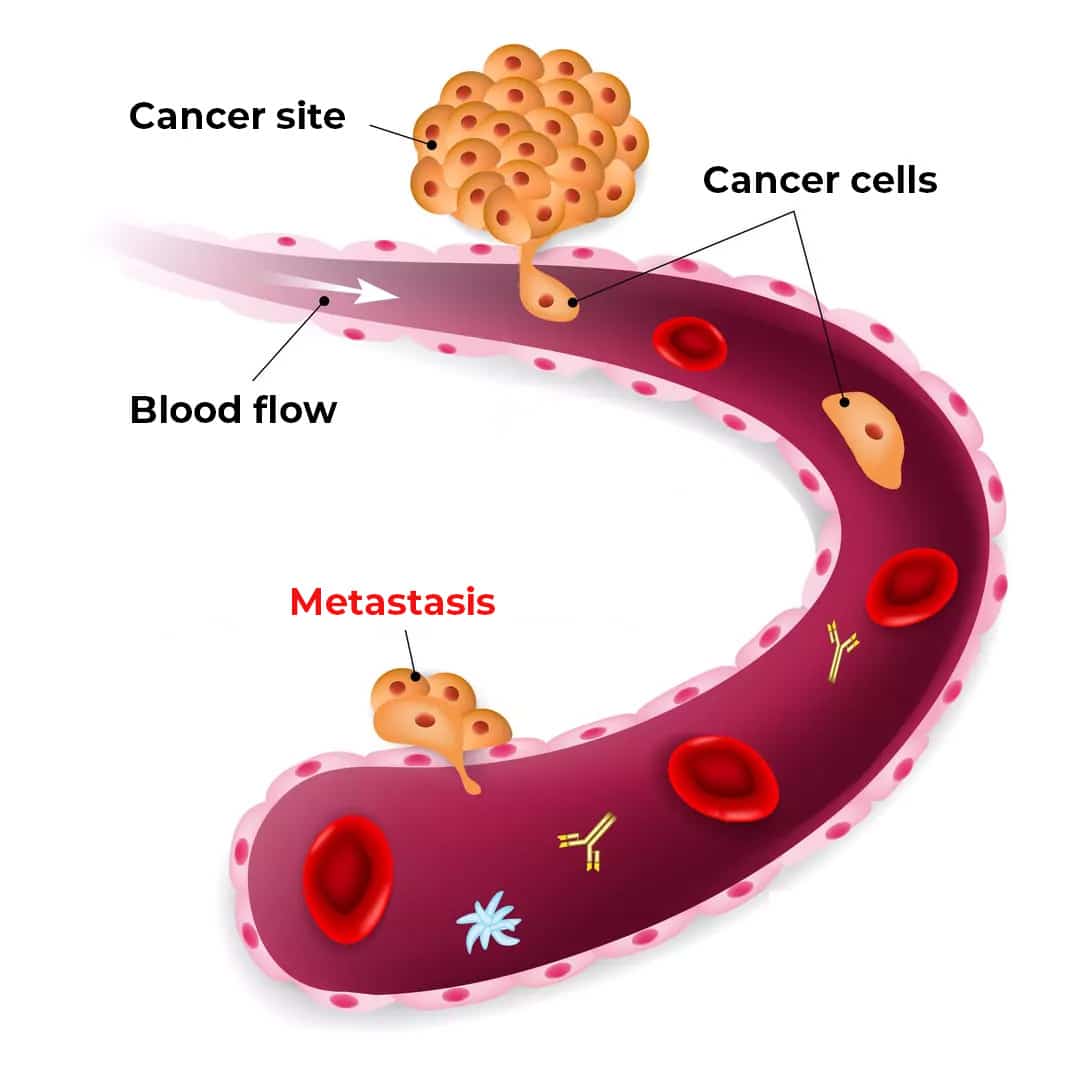

Sometimes, however, a NET may be diagnosed based on secondary diseases observed if the primary site (or main site) is not visible. Cancers are named and treated according to the organ where they originated, even if they have spread to other organs. For example, if a patient has an intestinal NET that has subsequently spread to the liver, this is referred to as an intestinal NET with “liver metastases” or “secondary tumours”.

It is generally easy to identify a primary cancer: it causes specific symptoms or is visible on a CT scan. However, it is sometimes the case that secondary cancers affect one or more organs without it being possible to identify the primary site. This is what we call a neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary (NET CUP). This doesn’t usually affect treatment options.

Lung NETs (also known as bronchial or pulmonary NETs) can be subdivided into five types:

- Typical lung NETs (also known as TCs, typical carcinoids) – These tend to exhibit a slow growth rate and are the most common lung NETs

- Atypical lung NETs (or AC, atypical carcinoids) – These can grow rapidly and tend to metastasise

- Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECHs) NETs – These are very rare and can cause the pulmonary neuroendocrine cells in the lungs to become too large. These tumours can be very small. The affected tumours don’t usually change significantly or rapidly, but DIPNECHs may be considered a precancerous condition and progress to typical or atypical pulmonary NETs.

- Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma – This is a rare form of pulmonary NET, similar to small cell lung cancer

- Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma – This is believed to be the most aggressive form of lung NET

Typical lung NETs account for almost 90% of cases. These grow slowly and rarely spread outside the lungs (less than 15% of cases).

Together, typical and atypical lung NETs represent 40% of all NETs.

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma are the rarest but most active lung NETs. They develop at the same rate as lung cancers.

This is an extremely rare type of NET.

It is generally diagnosed when tissue is analysed for more common types of breast cancer.

The adrenal glands are located on top of the kidneys and produce hormones involved in blood pressure control or stress management.

There are three types of neuroendocrine tumours that can appear inside or near to these glands: adrenocortical carcinomas, pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas.

- Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) – A cancer affecting the outer layer of the adrenal gland. It can cause the release of excessive amounts of hormones, including adrenaline, norepinephrine and steroids, which help the body maintain blood pressure as well as salt and sugar levels.

- Pheochromocytomas (pheos) and paragangliomas – These are rare tumours of the adrenal gland that originate in the inner part of the gland (medulla). Similar tumours can appear on the outside of the adrenal glands; these are paragangliomas (extra-adrenal).

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors are found in the stomach. There are three types:

- Type 1 – These NETs are usually small, and often multiple; they represent the least aggressive type.

- Type 2 – These NETs are associated with elevated stomach acid levels and also tend to be associated with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (or cluster of symptoms). These NETs are usually large and can metastasize.

- Type 3 – These are the largest gastric NETs and have a high risk of metastasis, making this type very aggressive. These NETs may not be associated with high levels of gastrin or stomach acid.

The liver is very rarely the primary site of a NET-type cancer. NETs present in the liver are often due to the spread (metastasis or secondary tumours) of cancer cells from another organ.

The liver is the most common site for secondary NETs. Its dominant role in body functioning and blood circulation promotes the formation of metastases.

The pancreas is an organ that produces insulin and other hormones.

There are two types of pancreatic NETs:

- Functional – These are pancreatic NETs that cause a specific set of symptoms (syndromes) such as insulinoma, gastrinoma, somatostatinoma, glucagonoma and VIPoma.

- Non-functional – Do not cause syndromes, but common symptoms include back pain, jaundice, stomach pain and weight loss.

Small intestine NETs (also known as jejunal, ileal or ileocaecal NETs) are the most common intestinal NETs.

They tend to grow slowly and may cause symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome or carcinoid syndrome, or may cause no symptoms at all.

Therefore, it can be difficult to benefit from an early diagnosis.

Tumours in the appendix that are less than 1 cm in size are often removed and cured with surgery.

Larger goblet cell NETs are a more aggressive form of appendiceal NETs and tend to spread.

Ovarian NETs are often secondary NETs originating from a primary site in the bowel or appendix.

Primary ovarian NETs are extremely rare. To date, two types of tumours have been identified:

- Ovarian neuroendocrine tumours (NETs), which are slow growing (low to moderate grade).

- Ovarian neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC), which behave more like ovarian cancers (high grade) and can cause carcinoid syndrome.

Gynaecological NETs (uterus, cervix, vagina and vulva) are very rare. They are usually only diagnosed when tissue is examined for signs of other cancers that are more commonly found in these areas.

Two types of tumours are found in the uterus and the cervix:

- Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) – These are tumour cells that grow more slowly.

- Neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) – These are more aggressive tumours which tend to grow faster and spread beyond their primary site, potentially leading to the development of secondary tumours in other organs.

Vagina and vulva NETs are the rarest type of NETs. They are classified in the same way as NETs of the ovary, i.e. as neuroendocrine carcinomas and neuroendocrine tumours. NETs of the testicles and prostate

As with NETs of the female reproductive system, NETs of the testicles and prostate can be classified as carcinomas or tumours, depending on how the cells look under a microscope.

Colonic NETs are rare and can cause symptoms such as a change in bowel habits, abdominal or stomach pain, weight loss and bleeding, which are similar to symptoms of its more common counterpart, bowel cancer. Colonic NETs are usually aggressive and have a tendency to spread.

Rectal NETs can cause bleeding, constipation or pain when defecating (opening the bowels) but cause no symptoms – which can delay diagnosis.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and aggressive type of skin cancer that forms on the surface or in the top layers of the epidermis. It starts to develop in neuroendocrine cells known as Merkel cells. These cells secrete hormones into the blood when they are stimulated by the nervous system.

The thyroid is a gland located in the neck, which produces hormones that affect blood pressure, body temperature, heart rate and metabolism.

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is a rare form of cancer of the thyroid gland. This gland is part of the endocrine system.

There are two types of MTC:

- Sporadic MTC (or isolated MTC), when a patient has no family history

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (or MEN2), in the case of an inherited (genetic) disorder

There are three distinct variants of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MENs): MEN1, MEN2, MEN3 (types 2 and 3 are also known as MEN2a and MEN2b).

MEN syndromes are inherited disorders. MEN disorders lead to the development of growths (tumours) in several glands of the endocrine system. The affected glands then secrete abnormally high levels of hormones – the body’s chemical messengers – which, in turn, leads to the appearance of various symptoms. Each growth can develop alone or independently of the MEN (referred to as an “associated endocrine growth”).

Other syndromes exist, less common. We invite you to discover our NET Handbook, in which you will find more information.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SYMPTOMS AND SYNDROMES

When we talk about NETs, we often talk about symptoms and syndromes.

A syndrome is set of specific symptoms. A NET associated with a particular syndrome means that the patient experiences a particular set of symptoms.

This type of syndrome appears when the NETs release excessive quantities of hormones into the blood. Its typical symptoms are:

- Hot flushes: redness on the chest and face, occasionally the whole body

- Abdominal cramps

- Diarrhoea

- A loss or reduction in appetite

- A rapid heart rate that may be accompanied by a hot flush

- Stomach and/or abdominal pain

- Fatigue

- Changes to skin

- Carcinoid heart disease

This syndrome is also known as carcinoid heart disease or CHD. Carcinoid heart disease is a syndrome caused by serotonin (a hormone).

When a NET causes excessive amounts of serotonin to be released, fibrous deposits sometimes build up on the heart valves.

This situation can prevent them from opening and closing normally, which disrupts blood circulation and can cause shortness of breath and severe fatigue.

This syndrome is usually caused by insulinomas, which are tumours of the pancreas that cause an excessive release of the hormone insulin. Insulin lowers blood sugar, and too much insulin can cause an excessive drop in blood sugar, which can lead to a whole host of problems.

Hypoglycaemia is characterised by the following symptoms: sweating, hunger, dizziness, unusually pale appearance, confusion and irritability. If sugar levels drop too quickly and reach levels that are too low, you may also faint or have seizures.

It is not uncommon for people with insulinoma to gain weight because they experience symptoms such as hunger and dizziness, and therefore eat more in response to this (sometimes every two hours to lessen these symptoms).

Whipple’s triad: Symptoms of hypoglycaemia with low blood sugar that are easily relieved by eating sugar or foods that are high in sugar.

The Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES) can manifest when NETs in the pancreas and duodenum release excessive amounts of the hormone gastrin into the blood. Gastrin helps control the release of stomach acid, which allows the breakdown of starch in food. Symptoms can include acid reflux, heartburn, stomach or even chest pain, belching, diarrhoea and anaemia (low iron).

Excess gastrin can also cause gastric and/or duodenal ulcers and bleeding from the gastric or duodenal mucosa. Gastrin levels can be checked with a blood test. If you are taking medicines known as PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) for problems like heartburn and acid reflux, you may be asked to take another medicine or stop taking PPIs before proceeding with the blood test to ensure the accuracy of your results.

The Verner Morrison Syndrom (VMS) can be caused by a VIPoma, a type of NET that is located in the pancreas. Symptoms include very watery diarrhoea, low levels of potassium in the blood and low levels of hydrochloric acid in the stomach.

These can occur when VIPomas release too much vasoactive intestinal peptide into the blood.

The symptoms of an Necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) include a rash on the body, which is sometimes mistaken for eczema. Sometimes referred to as a glucagonoma, it also causes weight loss, diabetic-like symptoms (high blood sugar, feeling excessively thirsty and hungry, frequent urination at night), diarrhoea, blood clots and changes to the skin, nails and hair.

There are also other, less common, syndromes. We recommend reading our NET Handbook for further information.

JARGON OF NETs – Acronyms used

Different acronyms are used to describe the different types of NETs. Here are a few that are commonly used in medical language:

“pNET”: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours or neuroendocrine tumours located in the pancreas.

“F-pNET”: Functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours or NETs located in the pancreas that manifest with a range of specific symptoms.

“NF-pNET”: Non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours or NETs located in the pancreas that do not manifest with a series of specific symptoms.

“NET CUP”: Cancers of unknown primary, which means that your tests did not reveal where your NET originated.

“GEP NET”: Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours or tumours that are located in the bowel or pancreas.

“GI NETs”: Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours or NETs that are located in the oesophagus, stomach or bowel.

“NEN”: Neuroendocrine neoplasms, which is another term for NET (neoplasm means “new growth” or tumour).

“SiNEN”: Neuroendocrine tumours in the small intestine.

“gNEN”: Gastric neuroendocrine tumours or NETs found in the stomach.

“dNEN”: Duodenal neuroendocrine tumours.

“MANEC”: Tumours that contain NET cells and more common cancer cells.

“NECs”: Neuroendocrine carcinomas, NET cells that behave more aggressively and are most likely to spread. They behave more like common cancers.

STAGES

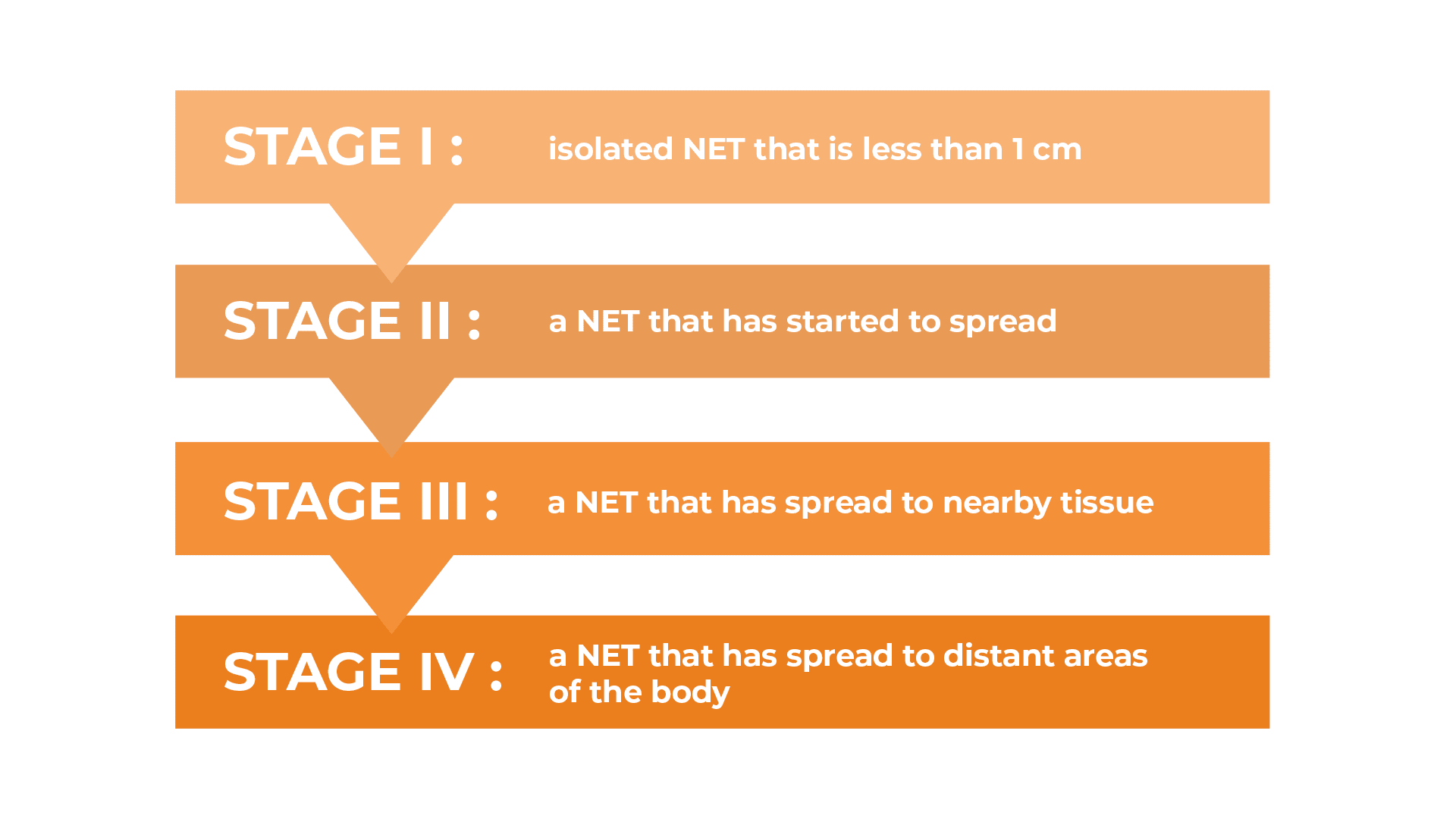

When we talk about a tumour, we talk about where it is located and how it has spread.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) provides a useful benchmark: a 4-stage system for classifying NETs.

All NETs are classified according to a similar scale.

Stage I: an isolated NET that is less than 1 cm in diameter and has not spread to surrounding tissue or anywhere else.

STAGE II: a NET (usually more than a centimetre in diameter) that has started to spread to nearby tissue or structures but has not spread to other parts of the body or to the lymph nodes (the tiny glands that help fight infection).

STAGE III: a NET of any size that has spread to nearby tissue and structures and to a lymph node.

STAGE IV: a NET, no matter how small, that has spread to distant areas of the body, such as the liver and one or more lymph nodes.

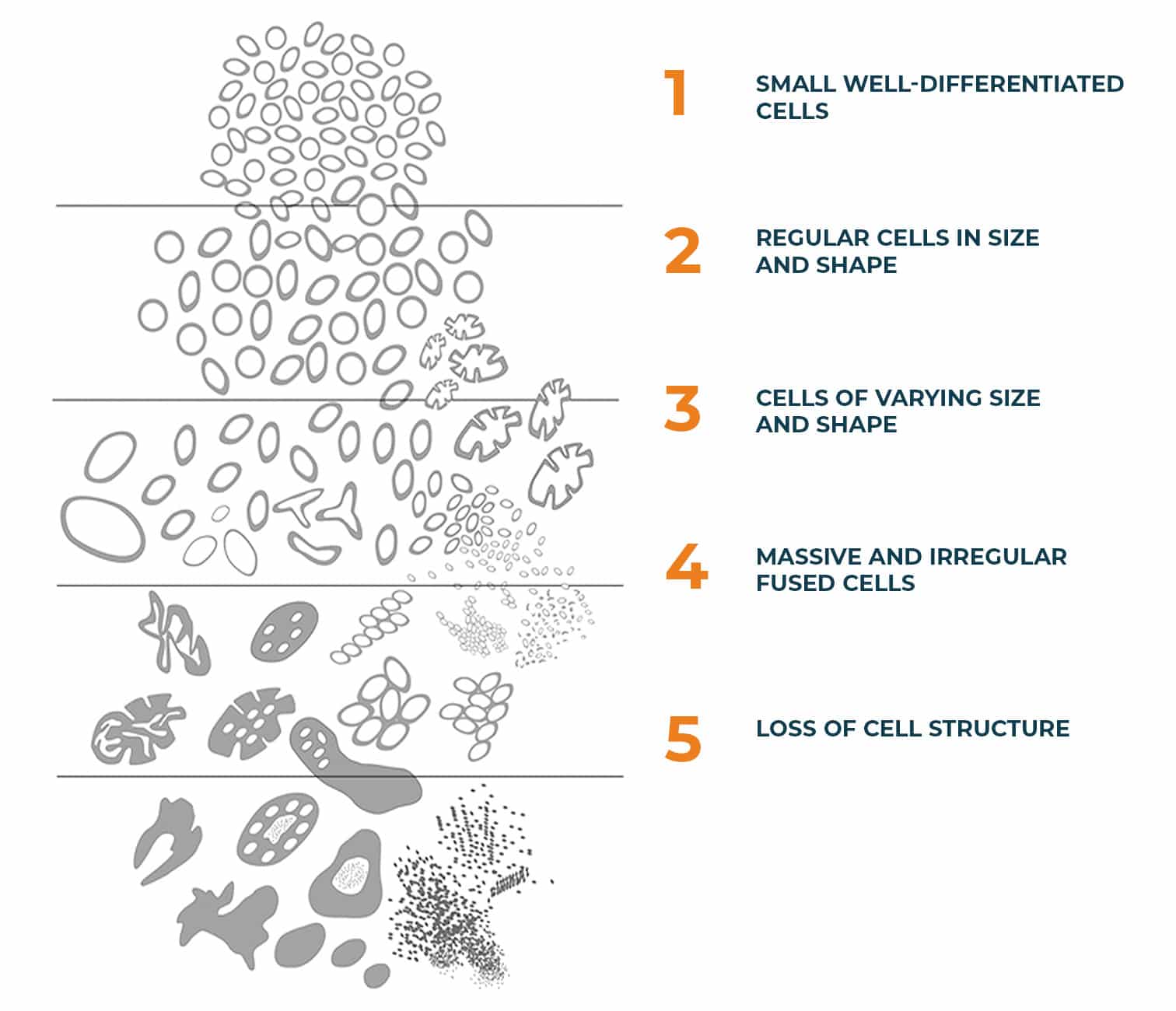

GRADES

The grade of a NET is based on how the cells look under a microscope (differentiation) and how quickly they divide to form new cancer cells. The medical team assigns a grade to the NET(s) so that they can choose the most appropriate treatment. To understand the grades, we first need to understand the difference between a NET cell and a healthy cell.

Here is the classification of NETs by the World Health Organisation:

GRADE I: a NET with well-differentiated cells, less than 3% of which divide.

GRADE II: a NET with well-differentiated cells, less than 3% of which divide.

GRADE III: a NET with well-differentiated cells, more than 20% of which divide.

GRADE IV: a tumour known as a neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) rather than a NET, which has poorly differentiated cells, more than 20% of which divide.

WHY THE ZEBRA?

When researching neuroendocrine tumours (NETs), you have probably noticed a zebra-print ribbon; this is the emblem of neuroendocrine cancer. This type of cancer is rare, just like the animal. NETs are often compared to zebra stripes: no zebra is the same, just like every patient is unique, both in terms of their diagnosis and in their treatment.

World NET Cancer Day takes place on 10 November and is coordinated by the International Neuroendocrine Cancer Alliance (INCA). This day is marked to raise awareness among the general public and health professionals about this rare form of cancer which is difficult to detect and often misdiagnosed. The aim is to improve the diagnosis, care and quality of life of patients.

#LetsTalkAboutNET #VictoryNETfoundation

ABOUT US

NET TUMOURS

- © 2022 Victory Net Foundation

- Legal information

- Designed by webgeneve

- © 2022 Victory Net Foundation

- Legal information

- Designed by webgeneve